Breeding

When to Start and Stop Breeding

When Do Queens Go Into Their First Heat?

When Are Studs Able To Sire Litters?

Sexual maturity for Studs can start at as early 6 months. They will go through major growth spurts, start spraying to mark their territory, caterwaul to serenade and attract mates, and lastly, will show interest in mounting Queens. While they may be exhibiting all the right signs, often times there's a steep learning curve for Studs. The mating act itself takes time to gain confidence and master. Therefor, Studs usually aren't able to actually start Siring litters until they're 10-12 months old. Even then, the litter sizes may be initially small as the Studs won't be successfully mating as often as they will when they've gained experience.

When Can I Start Breeding My Queen?

Age isn't as important as weight and appetite since ultimately that is what determines if a pregnancy can be safely maintained and even litter size itself. I have an 8 month Queen right now (Tundra) whom is as big, if not bigger, than her mother (Desert Rose)! So she is ready to start Breeding for sure. I also had a 6 month Queen (retired now, Bedazzle) whom had a silent heat (showed no signs). While I normally wouldn't have allowed a Queen as young as 6 months to mate, she took matters into her own hands! Turns out, she knew what she was doing. This girl had an appetite like you wouldn't believe. She would eat anything and a lot of it. Her first litter, at 8 months old, was with 7 kittens! All big, healthy kittens that she had no problem taking care of. Her appetite more than made up for any energy deficiency a pregnancy and subsequent nursing would have given. The younger then normal pregnancy also never stunted her growth and she went on to have a long and productive Breeding career before retiring as a spoiled pet.

How Often Do I Breed My Queen?

Bengals, specifically as a Breed, are more prone to a type of uterine infection known as Pyometria. The reason for this predilection is that when Queens go into heat their cervix dilates to allow for the entry of sperm. Unfortunately, it also allows for the entry of bacteria as well that exists normally within the vaginal wall. When not bred, Bengals stay in heat much longer then most other breeds, allowing them to stay at risk for a longer period of time (7-14 days Vs 3-5 days). However, when bred, Bengals stay in heat as long as most other breeds. Therefor, to prevent the risk of Pyometria, Bengal Queens are best to Breed as often as is possible.

That being said, I am a big believer that biology/nature developed over millennia to function the best way possible. As I've mentioned before, weight is the key. Once a Queen is at the correct weight (not age) to sustain a pregnancy, they're able to go into heat for the first time. Once kittens are born, the continuing drain on energy/weight is what keeps the Queen from going back into heat. If the drain on resources/weight isn't sufficient enough, like in the case of a small litter, the Queen is more likely to gain the weight back needed to sustain a pregnancy and they go back into heat. Typically, a Queen will gradually wean her kittens and then will go back into heat. This naturally lends itself to a healthy Queen having litters roughly every 5-6 months.

Disparity In Breeding Age Of The Sexes

So if Studs can't sire until 10-12 months and Queens go into heat at 8-10 months, then exists a natural disparity in ages between the sexes. Due to an increased risk of Pyometria in Bengal Queens that don't breed, it is important to make sure your Stud is ready for her when she goes into heat. You can usually safely skip the first heat cycle if needs be, maybe the 2nd as well, but it becomes increasingly unsafe to continue skipping cycles. It is, therefor, best to have your Stud 2-4 months older then your Queen.

When Do I Retire My Queen/Stud?

Generally, many Queens can continue breeding until 5-6 years old. Some will retire early due to many other factors (infection, C-section, complications etc.) There are many ways to tell it is time to retire your Queen, any number of them will satisfy the need:

Studs do not suffer from cycles of weight loss/gain as Queens do. So their fertility can last longer, up to 7-8 years. Most of the same signs for retirement in a Queen also hold true for Studs.

As you can see, fertility is complex. It involves both the Queen and the Stud. Age of either can play a critical part.

- 80% will at 8-10 months old

- 20% will at 6-8m or 10-12 months old

When Are Studs Able To Sire Litters?

Sexual maturity for Studs can start at as early 6 months. They will go through major growth spurts, start spraying to mark their territory, caterwaul to serenade and attract mates, and lastly, will show interest in mounting Queens. While they may be exhibiting all the right signs, often times there's a steep learning curve for Studs. The mating act itself takes time to gain confidence and master. Therefor, Studs usually aren't able to actually start Siring litters until they're 10-12 months old. Even then, the litter sizes may be initially small as the Studs won't be successfully mating as often as they will when they've gained experience.

When Can I Start Breeding My Queen?

Age isn't as important as weight and appetite since ultimately that is what determines if a pregnancy can be safely maintained and even litter size itself. I have an 8 month Queen right now (Tundra) whom is as big, if not bigger, than her mother (Desert Rose)! So she is ready to start Breeding for sure. I also had a 6 month Queen (retired now, Bedazzle) whom had a silent heat (showed no signs). While I normally wouldn't have allowed a Queen as young as 6 months to mate, she took matters into her own hands! Turns out, she knew what she was doing. This girl had an appetite like you wouldn't believe. She would eat anything and a lot of it. Her first litter, at 8 months old, was with 7 kittens! All big, healthy kittens that she had no problem taking care of. Her appetite more than made up for any energy deficiency a pregnancy and subsequent nursing would have given. The younger then normal pregnancy also never stunted her growth and she went on to have a long and productive Breeding career before retiring as a spoiled pet.

How Often Do I Breed My Queen?

Bengals, specifically as a Breed, are more prone to a type of uterine infection known as Pyometria. The reason for this predilection is that when Queens go into heat their cervix dilates to allow for the entry of sperm. Unfortunately, it also allows for the entry of bacteria as well that exists normally within the vaginal wall. When not bred, Bengals stay in heat much longer then most other breeds, allowing them to stay at risk for a longer period of time (7-14 days Vs 3-5 days). However, when bred, Bengals stay in heat as long as most other breeds. Therefor, to prevent the risk of Pyometria, Bengal Queens are best to Breed as often as is possible.

That being said, I am a big believer that biology/nature developed over millennia to function the best way possible. As I've mentioned before, weight is the key. Once a Queen is at the correct weight (not age) to sustain a pregnancy, they're able to go into heat for the first time. Once kittens are born, the continuing drain on energy/weight is what keeps the Queen from going back into heat. If the drain on resources/weight isn't sufficient enough, like in the case of a small litter, the Queen is more likely to gain the weight back needed to sustain a pregnancy and they go back into heat. Typically, a Queen will gradually wean her kittens and then will go back into heat. This naturally lends itself to a healthy Queen having litters roughly every 5-6 months.

Disparity In Breeding Age Of The Sexes

So if Studs can't sire until 10-12 months and Queens go into heat at 8-10 months, then exists a natural disparity in ages between the sexes. Due to an increased risk of Pyometria in Bengal Queens that don't breed, it is important to make sure your Stud is ready for her when she goes into heat. You can usually safely skip the first heat cycle if needs be, maybe the 2nd as well, but it becomes increasingly unsafe to continue skipping cycles. It is, therefor, best to have your Stud 2-4 months older then your Queen.

When Do I Retire My Queen/Stud?

Generally, many Queens can continue breeding until 5-6 years old. Some will retire early due to many other factors (infection, C-section, complications etc.) There are many ways to tell it is time to retire your Queen, any number of them will satisfy the need:

- consistently small litter sizes (1-2)

- many miscarriages 2+ (these should be rare)

- consistently having labor complications

- high stillborn rate or newborn death

- not going into heat

Studs do not suffer from cycles of weight loss/gain as Queens do. So their fertility can last longer, up to 7-8 years. Most of the same signs for retirement in a Queen also hold true for Studs.

- giving fertile Queens small litter sizes

- giving fertile Queens miscarriages

- giving fertile Queens a higher stillborn rate and newborn death

- not getting Queens pregnant

As you can see, fertility is complex. It involves both the Queen and the Stud. Age of either can play a critical part.

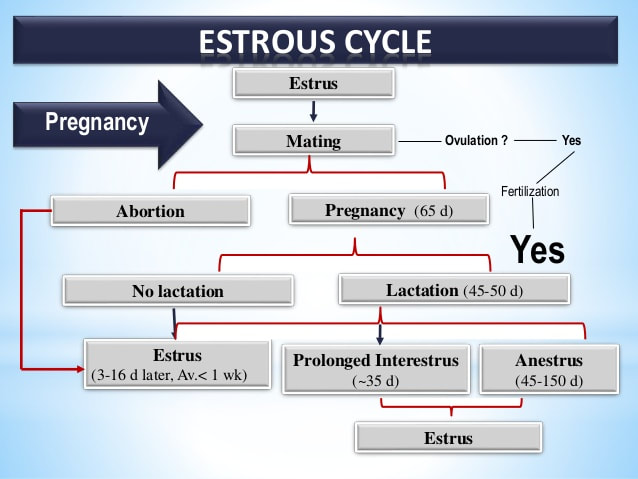

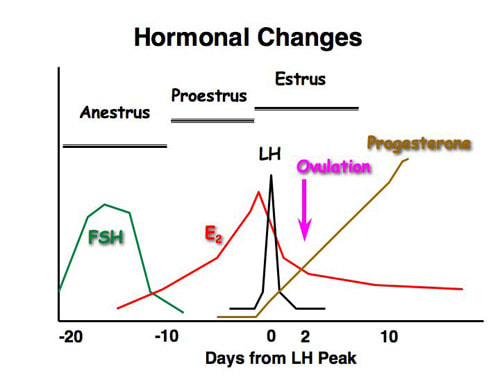

Different Stages of the Feline Reproductive Cycle

|

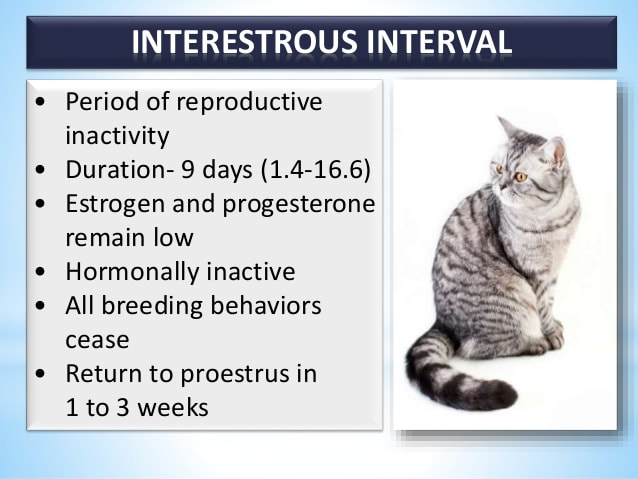

INTER-ESTROUS INTERVAL:

During the mating season when cycling through the various stages, this is the stage of hormonal rest. Happens before a heat cycle, after a heat cycle if unsuccessful impregnation happens, after a miscarriage, and after kittens are born. Indoor breeding, with artificial light, often creates a situation in which Breeding season is all year round. |

|

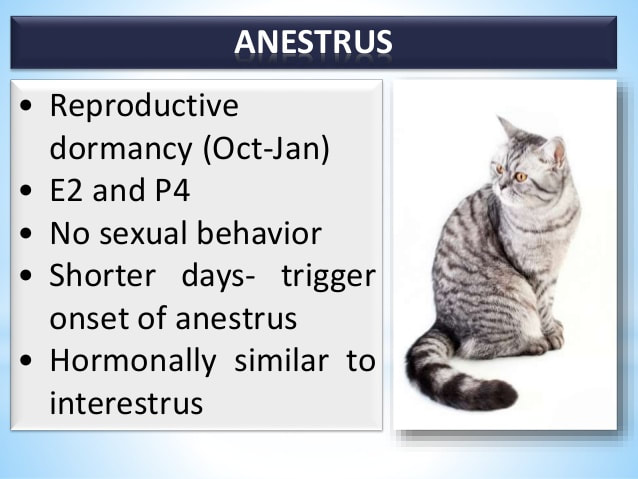

ANESTRUS:

Very similar to Inter-Estrous Interval. A complete Reproductive dormancy resulting in not cycling at all. It can be induced by time of year (seasonal mating periods), significant illness, chronic energy deficit, and possibly age. The mating season is often triggered by longer light exposure, which triggers the Pineal gland to suppress melatonin. During the off season when there is low light exposure, more melatonin is produced. Melatonin is known to repress the reproductive pathway and is often used by breeders to create breaks from breeding. |

|

PRO-ESTRUS:

This is the period in time at the beginning of the Heat cycle. At this point, the Queen will start vocalizing to let other Tom cats in the area know that they will soon be receptive. They are not willing to mate yet, as they want to give time for as many potential male mates to come to the call. Cats are polygamous and will want as many mates as possible. It is not unusual for a single litter to have multiple fathers. This helps to increase genetic diversity. Age of 1st heat for females: 70% 8-10 months old, 30% 6-8 months or 10-12 months Age males are effective at impregnation: 10-12 months old |

|

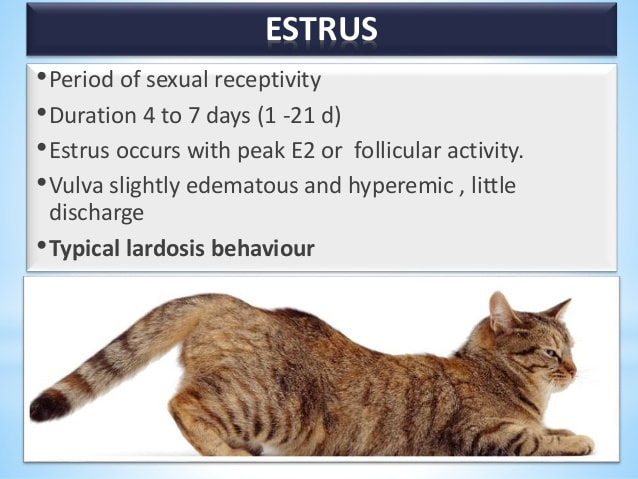

ESTRUS:

The Queen is now receptive to mating. She will readily get into the mating position, behind raised and tail turned to the side. In general, the shorter the estrus period the higher the probability of successful impregnation. Increase her food intake to raise the likelihood of a larger litter. When in Estrus, the feline cervix will dilate to allow the entry of sperm. This can also allow for bacteria that already exists as normal flora in the vaginal canal to invade the uterus causing an infection, known as Pyometria. Solution: mating. It will decrease the amount of time in estrus with a dilated cervix. This is particularly problematic for the Bengal breed since their heat cycles, when not mating, lasts longer then most other breeds. Mating = decreased heat cycle = decreased opportunity for Pyo |

|

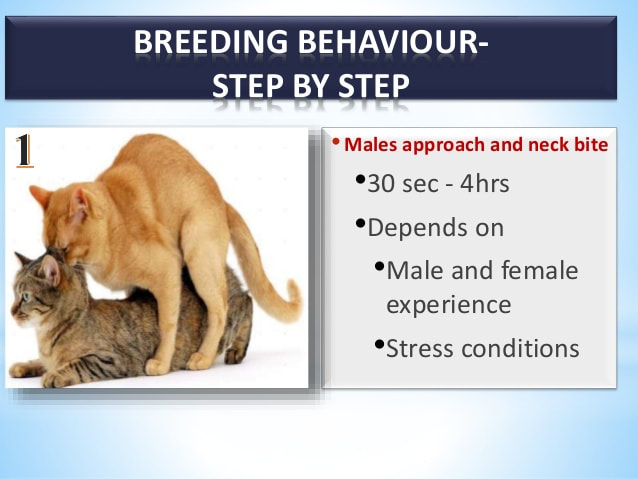

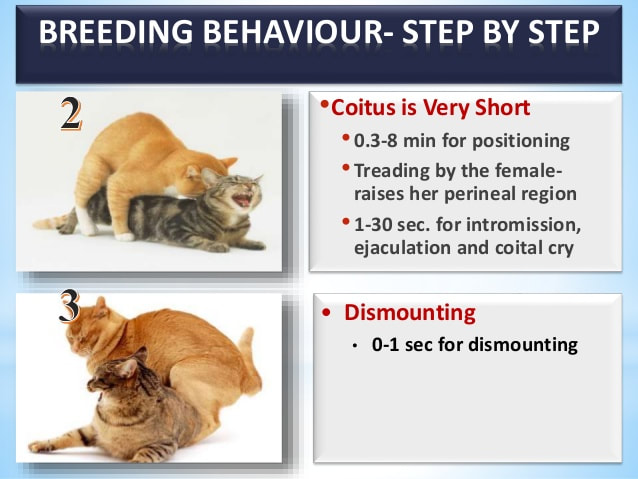

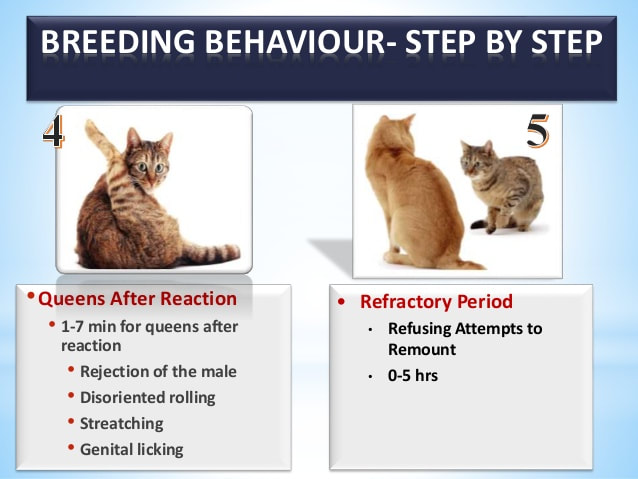

BREEDING BEHAVIOR:

Both males and females will spray pheromone ladened pee in order to attract a mate and reveal a number of important features, such as the hormonal and health status. The reason males get the bad reputation is because they're essentially in 'heat' all the time. They don't cycle like the females do. However, females will also spray when in heat. Likewise, males will caterwaul incessantly all the time whereas when females do, it's one of the hallmarks of being in heat. |

|

BREEDING ISSUES:

Some Queens are more difficult. They will be within the receptive stage but will still rebuke the advances of the Stud. In these cases, the Stud needs to be more forceful and experienced enough to overcome this obstacle. Also, some Queens are known to be "side winders". A term I use when the Queen is bitten on the back of the neck and instead of holding their mate position, they will start the next stage and try to roll on the ground. Experienced and determine studs are known to help keep a Queen in the correct position with his legs. |

|

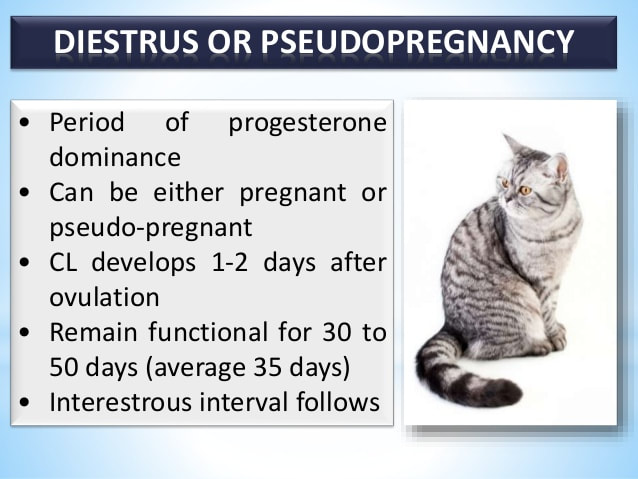

DIESTRUS/PSEUDOPREGNANCY:

There are 3 outcomes after Estrus.

Inducing ovulation is complex:

|

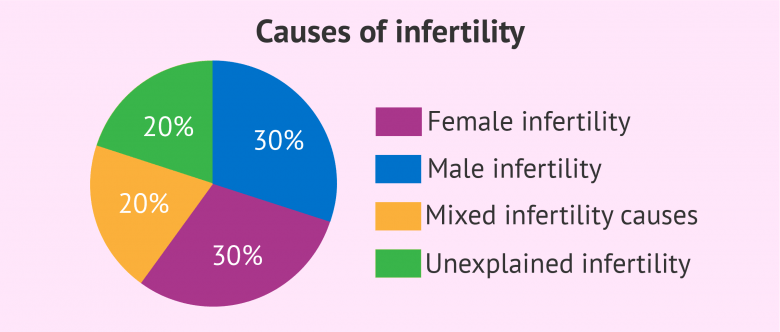

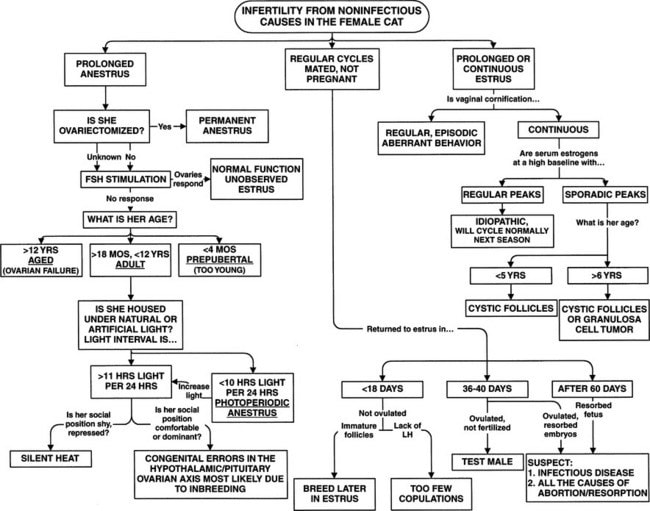

Infertility Issues

|

CAUSES OF INFERTILITY:

There are many: behavioral, hormonal, structural, pathological. To complicate matters, it can be from either partner or even both! The #1 cause of infertility is: absence of/insufficient amount of breedings. This can be for many reasons:

hair mats around penis makes erection painful back pain, physical discomfort |

|

INFERTILITY IN FEMALES:

Behavioral: failure to mate => doesn't cooperate with mating, environmental stress, breeding to early/late in estrous Hormonal: failure to cycle, abnormal cycles, failure to conceive, failure to keep pregnancy, hormonal imbalance, inadequate daylight, cystic endometrial hyperplasia (an age-related change in the uterine lining) Structural: chromosomal abnormalities, hermaphroditism, abnormal uterine or ovarian development, previous uterine infections (scarring), previous C-section (scarring), Pathological: parasites, ovarian cysts, tumors, FeLV, FIV, calicivirus, panleukopenia, herpesvirus, or bacterial infections: Pyometria, G-strep, UTI, inflammation of uterus from other causes. |

Recommended Testing:

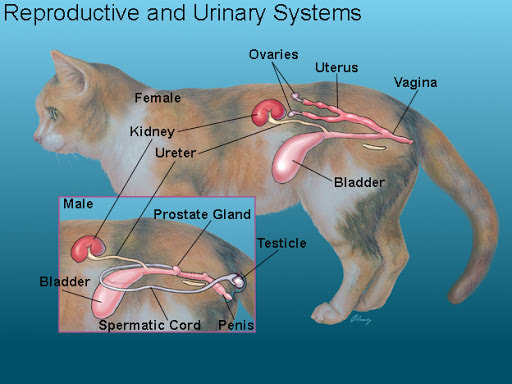

1. Laboratory testing. Screening bloodwork, including thyroid levels, can be used to assess your cat's overall internal health and look for possible causes of infertility. A urinalysis may also be performed, to assess for the presence of urinary tract disease (as the urinary and reproductive tracts are related).

2. Infectious disease testing. FeLV and FIV are common causes of feline infertility; therefore, your veterinarian will test your cat for these conditions. Other infectious disease testing may also be performed, depending on your cat’s clinical signs and history.

3. Vaginal cytology. In this test, your veterinarian will take a swab from your cat’s vagina and examine it under a microscope. Characteristic types of cells seen on cytology will allow your veterinarian to determine what stage of the estrous cycle your queen is in.

4. Vaginal culture. A sample of vaginal material may be submitted for bacterial culture, to assess for the presence of infection.

5. Hormone assays. Analyzing blood levels of progesterone and estradiol can allow your veterinarian to better characterize the stage of your queen’s estrous cycle.

6. Imaging. Ultrasound may be used to assess your cat’s uterus and ovaries.

*Article by: By Catherine Barnette, DVM

1. Laboratory testing. Screening bloodwork, including thyroid levels, can be used to assess your cat's overall internal health and look for possible causes of infertility. A urinalysis may also be performed, to assess for the presence of urinary tract disease (as the urinary and reproductive tracts are related).

2. Infectious disease testing. FeLV and FIV are common causes of feline infertility; therefore, your veterinarian will test your cat for these conditions. Other infectious disease testing may also be performed, depending on your cat’s clinical signs and history.

3. Vaginal cytology. In this test, your veterinarian will take a swab from your cat’s vagina and examine it under a microscope. Characteristic types of cells seen on cytology will allow your veterinarian to determine what stage of the estrous cycle your queen is in.

4. Vaginal culture. A sample of vaginal material may be submitted for bacterial culture, to assess for the presence of infection.

5. Hormone assays. Analyzing blood levels of progesterone and estradiol can allow your veterinarian to better characterize the stage of your queen’s estrous cycle.

6. Imaging. Ultrasound may be used to assess your cat’s uterus and ovaries.

*Article by: By Catherine Barnette, DVM

|

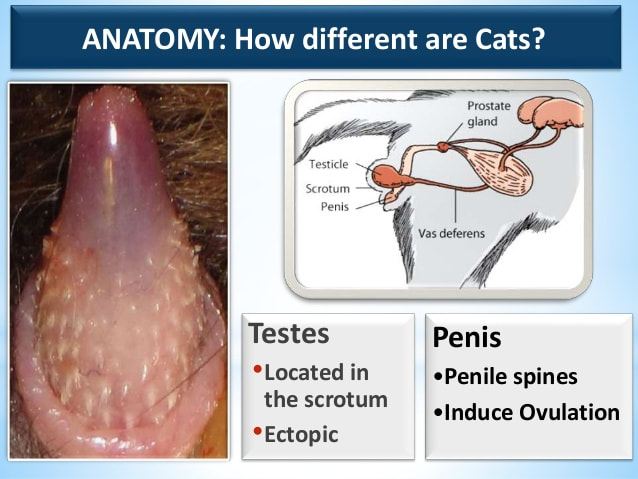

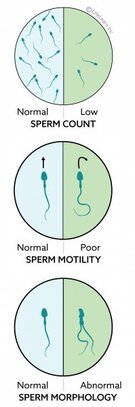

INFERTILITY IN MALES:

Behavioral: failure to mate => lazy (gives up easily), not experienced enough to deal with difficult Queens, doesn't prefer a Queen, environmental stress Hormonal: low testosterone Structural: retained testicles, malformed testicles, sperm issues (count, motility, morphology), disorders of the penis (hereditary or trauma): priaprism (persistent erection), paraphimosis (inability to retract the penis into the sheath), and phimosis (inability to extend the penis from the sheath) Pathological: testiscular disease, tumors, UTI, other systemic infections (FIV, FeLV, FIP) Recommended Testing:

1. Complete blood cell count and serum biochemistries.Screening bloodwork, including thyroid levels, can be used to assess your cat's overall internal health and look for possible causes of infertility. A urinalysis may also be performed, to assess for the presence of urinary tract disease. 2. Infectious disease testing. Tests to assess for viral infections such as FeLV, FIV, and FIP can aid in determining the cause of infertility. 3. Semen evaluation. If possible, your veterinarian will obtain a sample of your cat's semen for evaluation. Some tom cats can be trained to provide a sample for assessment, while others may require sample collection under anesthesia. Your veterinarian will examine the semen to ensure that the sperm are structurally normal, with normal motility (movement). 4. Testosterone testing. Circulating levels of testosterone can vary significantly in normal cats, depending on time of day and other factors. Therefore, assessing testosterone levels requires more specialized testing, such as a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) response test or a human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) response test. In these tests, a cat is injected with a hormone known to trigger testosterone release and testosterone levels are assessed 1-2 hours after this injection. 5. Abdominal imaging. X-rays and ultrasound may be used to evaluate internal structures, such as the testicles or prostate gland. *Article by: By Catherine Barnette, DVM |